Rival Reviews: Lyme Park

Colin Firth is like the Loch Ness Monster of Lyme Park. He’s not there, but it’s fun to imagine him in the lake anyway.

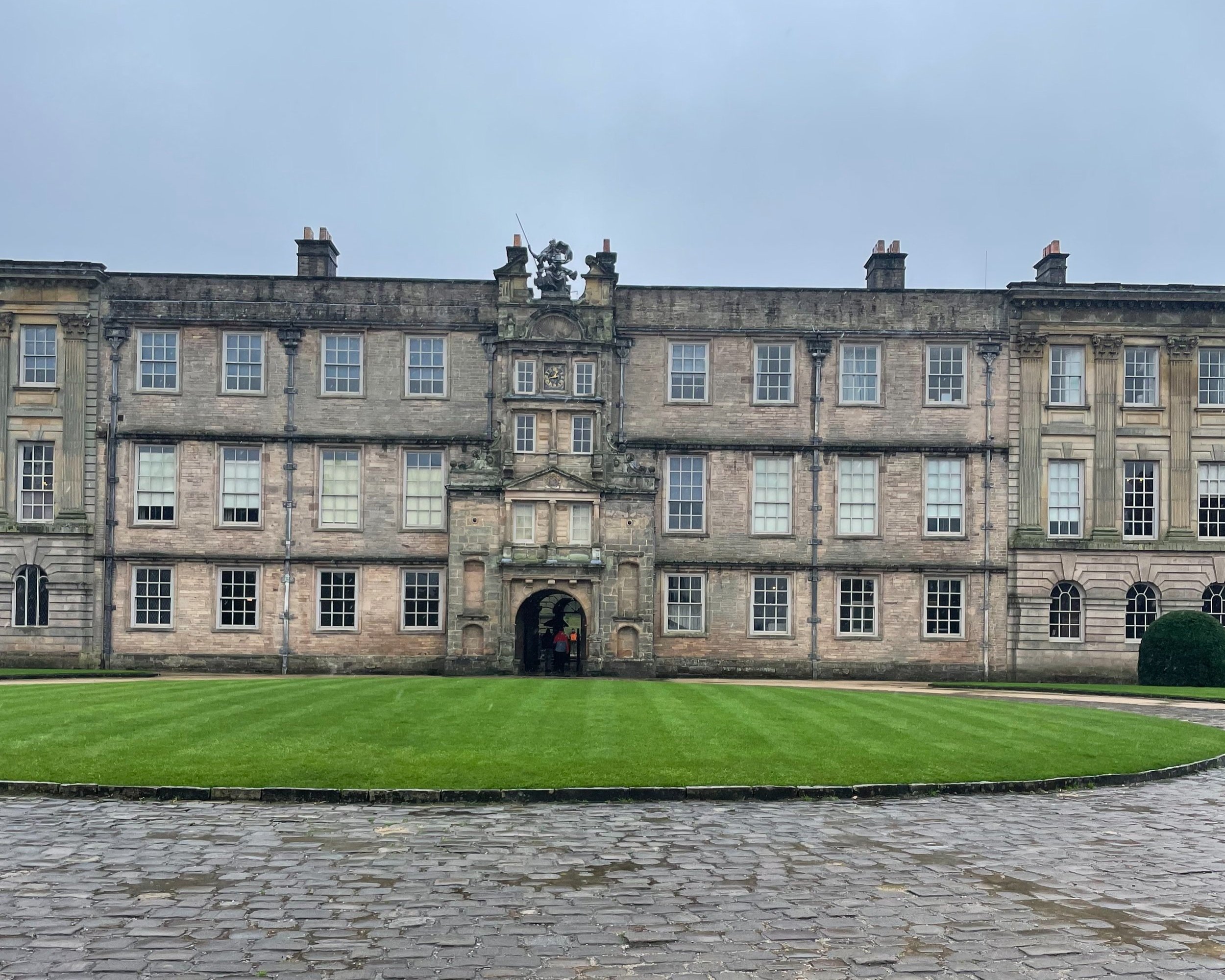

Lyme Park imposing under the grisly sky

Lyme Park is popularly remembered for its starring role as the fictional country estate Pemberly in the BBC’s 1995 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. The series famously features Colin Firth’s turn as Mr Darcy, which catapulted him to fame, and inspired Helen Fielding to write Bridget Jones’s Diary, also featuring Colin Firth also playing Mr Darcy - a different one though. This is acknowledged in the Lyme Park gift shop, where a large number of products featuring Colin Firth in regency garb are available for purchase and prominently featured. I got a mug. Also a magnet.

In its real history, Lyme Park has hardly less humble origins. The land where Lyme now stands was gifted to the Legh family in 1398, and since that day this great mansion has been built, rebuilt, enlarged, modified and embellished by its incumbents over the centuries, from a medieval hunting lodge to the Palladian-inspired house I stand in now.

The floating staircase

And what a house it is. The largest in Cheshire, the property is built around a central courtyard paved in pink and white stone to simulate marble. At the centre sits a Renaissance well-head, and a rusticated cloister (a covered walk, if you fancy) surrounds it on all sides. The whole thing is very Roman villa, transplanted to grisly Cheshire. This is no Lullingstone (Roman villa in Kent - not so grisly, but still Kent) however; one of the most popular architectural motifs in England for years was co-opting the classic in order to show off your own power, education and wealth. For example, Henry VIII chose a nostalgic medieval hammerbeam roof when redesigning the Great Hall at Hampton Court, knowing that imitating an older style would make the Tudor line look more established and evoke the era’s noble legends of bravery and daring-do. If even Henry VIII knew to do this, you know it must have been easy, and obvious. Through the evocation of a villa, the Legh’s were displaying their worldliness and education by associating themselves with upper-class Romans; implying the abundance of their wealth by associating themselves with upper-class Romans; and making a statement about the reach of their power by associating themselves with upper-class Romans. And this barely scratches the surface of the silent language of Georgian architecture.

The entrance is between the second and third floors, and accessible via stairs. I hesitated a long time wondering if this was in fact the way in, visions going through my head of a fate worse than even death: going up and trying to open a locked door in front of a smattering of young families and old couples. It’s raining, so it is relatively quiet here.

Once inside however (the entrance was in fact the unobvious door with no visible signage), I am enchanted. The National Trust does indeed dress a nice house. The parlour is resplendent in tapestry and laid out as if I had arrived by carriage and invitation in 1758, adorned in silks and chiffon, rather than by Ford KA and whim, adorned in polyester cotton blend.

I prepare myself to explore, trying to decide whether to use the guidebook I purchased on arrival or the in-room interpretation booklet and wondering how they are different and why this could be, when I am witness to the most shocking turn of events.

A young couple sharing the space are evidently taken by the instrumental features of the room, and soon the woman asks to go and play the piano on display in the lounge. Ridiculous, of course. It’s behind a red velvet rope! But she is admitted passage. Unprecedented. She explains to the volunteer that she restores antique pianos for a living, then she starts to play, stating the piano is out of tune. She plays the theme from the Pride and Prejudice feature film (2005), starring Kiera Knightley and Matthew MacFayden. I would recognise it anywhere.

Spirits significantly buoyed by this delightful turn of events, I only continue round the house when the song is done. In the saloon, I encounter the Sarum Missal and an ancient Greek stele (gravestone), the former the only surviving intact book of its kind, representing changing religious views at the close of the 16th century, the latter an archeological find from Athens. The Sarum Missal has been in Legh family hands from at least 1504 until it was purchased by the National Trust in 2008. It was the first copy to be printed, in the late 1400’s by William Caxton, the man who bought the printing press to England (he printed the Sarum Missal in Paris, however - what a rip off), and part of what makes it so special is that it retains some of its original binding. This book is the real deal.

But then Lyme has all kinds of little gems. In the entrance hall, a mounted picture on hinges swings open to reveal a squint, (or hagioscope, if you fancy), this is a small opening at eye level, usually found in a church to give worshippers a view through a wall to an altar. Here the squint gave Lord and Lady Legh a good peek at whoever was coming into their house. A painting with holes for eyes might have been more dramatic, but very slightly less dignified.

Apollo’s directory of available oracles

In the drawing room, I witness a sumptuous stained glass window depicting all the Oracles (a person or thing of prophecy and insight, like an oddly specific magic 8 ball) who worked under the line management of every upper class, well-educated, antiquity-loving, regency era’s favourite Greek god, Apollo. God of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more besides, Apollo is a frequent symbol through many 18th century homes.

In the gardens, the orangery is a particularly beautiful addition, designed in 1862. At this time, orangeries were having a moment. As the world expanded through travel, and more and more exotic plants were becoming known, the value placed on this conservatory predecessor became increasingly tied into garden design, and divorced from its previous haunts around kitchen gardens. So important as a symbol of the elite they became, that architects soon began to tie the orangery's design to the architecture of the house, and Lyme is no exception. Like many orangeries at the time, Lyme’s does not contain its titular fruit, but rather a variety of exotic plants that need its hot artificial climate to grow. False advertising perhaps, but worth a visit even in an era where acquiring an orange is as easy as locating the nearest corner shop.

The orange-free orangery

Finally, the grounds (different from the gardens - it’s bigger), are dotted with various buildings, used as hunting lodges, or accommodation for groundskeepers, among other things. One of their most important purposes however, was to be aesthetically pleasing. One building, known as The Lantern, so called because its octagonal shapes and spire make it look like a-, well anyway. Not content were the Legh’s with the vastness of their property itself, these little architectural delights were built as objects that would catch one’s eye as they gazed across those imposing grounds. Upping the scenic value of an already scenic view. This was often known as a belvedere (literal translation: beautiful view). As a lover of the occasional garden folly, I was suitably impressed.

Thus ended my visit at Lyme Park, despite walking round the lake more than once, I could not obtain a clear view of any type of regency gentleman in the water, but I did get my magnet. And my mug.

Lunch

Can’t go wrong with a hot sausage roll, though trying to eat it on the go will result in a burnt mouth and more crumbs on your coat than would be considered appropriate in polite company.

Stables or Kitchen?

Kitchen, with an extra cafe in the old beer keg store.

Can I take my dog?

Dogs will love a stroll through the grounds. They’re like little belvederes themselves, aren’t they? So cute!

Can I take my kids?

Kids would love the dress up opportunities abundant in this house.

Walks

Why not visit a belvedere up close? A healthy walk with a clear end goal in sight.

Well, what did you think?

An archetypal 18th century pad, Lyme Park is a fab day out and worth exploring. Overshadowed perhaps by its starring role, much like a child actor in a famous movie series, it has more to offer than Colin Firth in a lake, particularly as he’s not actually there. You know that, right? He’s not there.